How Learning Works, Ch. 3: Motivation, Disengagement, and the Importance of the Learning Environment

Posted: October 9, 2011 Filed under: How Learning Works 1 CommentThis chapter on motivation feels a bit more abstract than the earlier ones in How Learning Works, but it provides some theoretical underpinnings to the usual pragmatic “stuff that works” that experienced teachers often describe to their junior colleagues. It also helps us understand why these kinds of practices tend to have some effect on students, but also why they sometimes get neutralized by other factors in the classroom. Consequently, it adds a new dimension to the book’s earlier chapters on students’ prior knowledge and their organization and processing of new knowledge, by showing the role of motivation in driving students to acquire new information and master new skills.

The key, for me, is the chapter’s theoretical breakdown of the rather difficult concept of motivation into three contributing factors: goals (what organizes our behavior to act in particular ways), value (the value placed on attaining particular goals), and expectancies (the expectation that one can successfully attain a particular goal).

In many respects, this provides a more sophisticated breakdown of what we typically call “student engagement,” with some explanation of why certain practices help students engage with their instructor and fellow students, by adjusting students’ levels of motivation towards the course and its content. It also provides some feedback and direction to instructors when they are faced with visible signs of student disengagement, in the form of apathetic, evasive, or defiant behavior.

Effective teaching aligns, and reinforces these three motivational factors so that students have learning goals appropriate to the course’s content, see the value in learning these skills and content, and have appropriate expectancies (i.e., expectations) about which actions will bring about the desired outcomes and about their own capacity to succeed.

As we have seen repeatedly in this and other works on effective teaching, the key seems to lie in the instructor’s skill in communicating clearly the goals and demands of the course, explaining its implications for students for their own lives and careers, and then providing feedback that helps students recognize where they need to place additional effort to succeed.

So, for example, in handing out a reading assignment on Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, I might tell students

- that they need to read Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe carefully enough to remember its major characters, events, and themes for use in classroom discussion and their research projects (goals);

- that by learning these aspects of Crusoe they will know something important about the history of fiction and early eighteenth century attitudes towards colonization and conquest (value);

- that rereading and taking good notes are important for not just understanding the book but being able to research and write about it (outcomes expectancies), and

- that they have been practicing note-taking, discussion, and essay-writing with earlier books, and they did these more or less successfully, and were given feedback to do it better this time (efficacy expectancies)

All these actions by an instructor, and their accompanying explanations, over the course of a semester amount to the broader “learning environment” that can be experienced by students on a spectrum that runs from supportive to unsupportive. The learning environment could be considered the sum total of all classroom interactions, but students can readily distinguish between environments where a faculty member “goes the distance” to help people learn, or is available enough to provide additional guidance to the struggling, and classes where this does not happen.

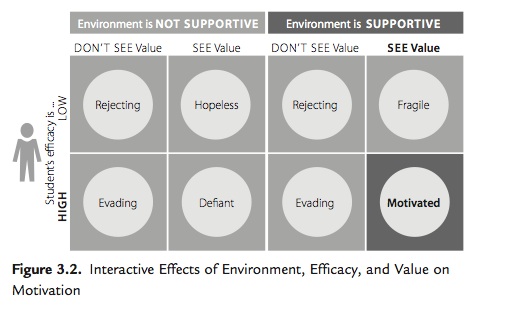

The figure 3.2 that I have reproduced from p. 80 of How Learning Works shows how students, in all their various levels of efficacy and perceived values, interact with their environment:

What we have here with this diagram is a redescription of the whole range of disengaged behavior visibly manifested by students (rejection, defiance, evasion, hopelessness, etc.), but with an explanation that shows how students arrived at these responses through a combination of preexisting attitudes and interaction with their instructor and environment.

For example, the low-efficacy student who sees no value in reading Robinson Crusoe will simply reject the assignment and fail to read it. The high-efficacy student who similarly fails to see the value would be capable of doing the reading, but chooses instead to scan a few pages and rely on a Sparxnotes summary. Note also that these responses occur in both the supportive and unsupportive classroom environments, if students place no value on learning the material.

This diagram is also useful because it suggests strategies to counter specific kinds of disengaged responses. One place to begin is to explain the value of learning the class content for students in the context of the class requirements, their major, and ultimately their post-graduate plans and careers.

The other aspect of this is addressing the efficacy of students, their own perceptions of how well they can direct their own learning to succeed at the goals of the course, as these are inflected by the environment they find themselves in. Students who understand the value of the course but feel themselves incapable will become hopeless and passive in an unsupportive environment, while those who understand it but feel that they are unsupported may go on to succeed at a course, but in an attitude of defiance.

From the perspective of motivation and student success, you want to find you and your students in the right-hand corner of the diagram: you want to see the competent, or high efficacy, students highly motivated and working hard our of their own sense of the importance of the material for their lives and careers, and you will recognize the lower-efficacy students in the “fragile” condition (upper right hand corner) wherein your feedback and their peers’ encouragement help shore up their efforts to improve.

Best of all, this diagram should help provide you with some feedback about your own success as a teacher in a course you are currently teaching: at any time, how many students of yours are manifesting signs of rejection or evasion? Who could be described as hopeless or defiant? What steps are you taking to articulate the goals of your course? What opportunities are you providing for students to identify and practice those skills that will help them in your courses and beyond?

So what do you do when you are midway through a semester, and you begin to notice these kinds of signs of disengagement? How do you undertake a mid-course correction when things like this go wrong?

That will be the topic for the TA-led panel, “Mid-Course Correction,” at our upcoming conference next Friday, Oct. 14th at 1:30-2:45. Our TA panelists will include Geneva Canino, English; Al Barnard, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences; Chris Nicholson, Political Science; Veronica Sanchez, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, with a response from our distinguished Plenary Speaker, Dr. James Lang (English, Assumption College).

See you then,

DM

How Learning Works, Ch. 2: How Does the Way Students Organize Knowledge Affect Their Learning?

Posted: September 4, 2011 Filed under: How Learning Works 2 CommentsThis chapter extends the principles discussed in the earlier chapter on prior knowledge, to alert teachers to the ways that students learn and process the material as it is presented to them.

This chapter focuses on the notion of student organization of material, and demonstrates that students’ organization of the material will differ from their teachers’ habitual organization of the material, or the way it is presented to them on a syllabus or in a textbook. These writers presnet examples of teachers presenting materials according to their own disciplinary schemas, only to learn that students quickly became confused or puzzled by the unfamiliar organization or sequencing of the material.

This is a routine problem in the college classroom, because an instructor’s immersion in the material, and her long-time specialist knowledge acquired over years, can sometimes become a disadvantage for communicating it effectively to first-time learners. As experienced scholars, researchers, instructors, we often forget what aspects of our discipline are most confusing to the novice.

This problem is illuminated in the discussion of novices vs. experts’ organization of material. The difference really lies in the complex, multidimensional organization of the material a trained expert brings to any material, even when it is new to them, while novices struggle to impose even the most minimal order on what they hear. The authors offer the following example:

As an illustration, consider two students who are asked to identify the date when the British defeated the Spanish Armada (National Research Council, 2001). The first student tells us that the battle happened in 1588, and the second says that he cannot remember the precise date but thinks it must be around 1590. Given that 1588 is the correct answer for this historical date, the first student appears to have more accurate knowledge. Suppose, however, that we probe the students further and ask how they arrived at their answers. The first student then says that he memo- rized the correct date from a book. In contrast, the second stu- dents says that he based his answer on his knowledge that the British colonized Virginia just after 1600 and on the inference that the British would not dare organize massive overseas voyages for colonization until navigation was considered safe. Figuring that it took about 10 years for maritime traffic to be properly organized, he arrived at his answer of 1590.

These students’ follow-up answers reveal knowledge organizations of different quality. The first student has learned an isolated fact about the Spanish Armada, apparently unconnected in his mind to any related historical knowledge. In contrast, the second student seems to have organized his knowledge in a much more interconnected (and causal) way that enabled him to reason about the situation in order to answer the question. The first student’s sparse knowledge organization would likely not offer much support for future learning, whereas the second student’s knowledge organization would provide a more robust foundation for subsequent learning (44-5).

There are a lot of implications for both course design and discussion in these principles: the first is that, at the level of the syllabus and sequence of topics (if you are responsible for these), you need to devise a logic that carries your students from topic to topic, and helps them make the transitions from one to the other until they reach the end. You will also need to monitor how they are organizing the material themselves, so that they are not simply memorizing facts but learning something of the concepts and principles that underlie the course’s content. Isolated facts tend to be displaced by other facts over time, but learning a principle that they can refine throughout the semester and in other courses helps give them a foundation for learning. We want them to know something about British naval power and how it operated in the seventeenth century, not an isolated fact.

The second principle is that on a day to day level, it’s a good idea to disclose the “agenda” for the day’s discussion, put it up for explicit discussion and if necessary elaboration at the beginning of class, and even close the class with a recap to make sure everyone “gets it.” And your own outline will be improved by your efforts to explain it to others, and by your repeated discussion of the core concepts and principles that emerge from the exchanges between you and your students.

DM

How Learning Works (ch. 1): Using the first day of class to discover your students’ prior knowledge

Posted: August 21, 2011 Filed under: CTE-DTAR, How Learning Works 2 CommentsAs promised, here is a link to How Learning Works, the text discussed at last Thursday’s Orientation for TAs. This publisher’s website offers pdfs of excerpts, along with links to order the book for yourselves.

Chapter 1 (which is available for free as Excerpt 1) features a good discussion of students’ prior knowledge, and describes in some detail how it affects their understanding of your course material. As the chapter reminds us, it is very risky to assume that you know what students know, or think they know, on the first day of a new class:

Students do not come into our courses as blank slates, but rather with knowledge gained in other courses and through daily life. This knowledge consists of an amalgam of facts, concepts, models, perceptions, beliefs, values, and attitudes, some of which are accurate, complete, and appropriate for the context, some of which are inaccurate, insufficient for the learning requirements of the course, or simply inappropriate for the context. As students bring this knowledge to bear in our classrooms, it influences how they filter and interpret incoming information (13)

The whole chapter is worth thinking about, but for now I’d simply recommend that you take a few minutes in your first class to ask your students about their prior knowledge of your subject-matter. This can be done informally, with a show of hands to a few questions, or more formally, by responding in writing to a brief survey or series of questions. Your questions could cover the following:

- Earlier courses taken in the subject, and the institution where these were taken (an important detail at a transfer-heavy school like UH)

- Their familiarity with a few key concepts in your subject area (ask them to elaborate on what they’ve learned about it from earlier courses)

- The distinction between ordinary language and your subject matter’s technical terms

Your job will be to assess where they are in their understanding of your subject matter, and then begin to the areas where they need to build, refine, or correct what they already know, or think they know. The first day is just the beginning of what will be a semester-long process of helping them to learn how to recognize and address their own gaps in knowledge.

Have a good first day,

DM